Veranda Tales-Drishti mantra to the rescue

Storytelling has been an integral part of my life since childhood. I grew up listening to stories during the hot summer evenings and nights with my cousins. Mothers and grandmothers would gather all of us children for story time. It was usually pitch dark except for a very faint light coming from the flickering candle. Power cuts were as frequent as the hot and humid summer days. We all spread out on a cool concrete floor or bamboo mats on the veranda intently listening to fascinating stories about kings, queens, princes, princesses, and peasants alike. Stories about love, life, families, and people entertained and taught us life skills. These stories transported us to distant worlds, strange yet familiar. Often the same story told by two people sounded different as storytellers added new twists and turns adding their personal style and flair to the stories.

Storytelling wasn’t limited to summer evenings and bedtime. I was surrounded by adults who didn’t pass up an opportunity to share their wisdom using the art of storytelling. These rich vibrant oral traditions include songs, poems, stories, and సామెతలు (Sametalu are proverbs in Telugu). Men and women sing songs as they work in the fields, grinding grains and spices and doing other daily chores at their homes. Stories are often used to teach important life lessons, interpersonal skills, and survival skills. These stories and the time spent listening to them made our lives richer leaving an impression on me. This series is all about reliving those memories as I share these stories.

చదివిస్తే ఉన్న మతి పోయినట్లు (chadivesthe unna mati poyinatlu)

I was an absent minded teenager lost in my thoughts, books, and daydreams. అమ్మ (Amma) would tease me by saying, “She would still be sitting there with her book even if lightning bolt strikes right next to her”. Whenever I did my absent minded things, అమ్మ (Amma’s) go to phrase was, “చదివిస్తే ఉన్న మతి పోయినట్లు (chadiviste unna mati poyinatlu)” as she shook her head while saying it. The literal meaning of this sameta is, “after educating a person, they lost the mind they had before the education''. It means when someone is sent to school to learn and get education, they forget what they knew before.

She was convinced that if I was left to my devices I wouldn’t even eat. She didn’t need to remind me to get ready for school or do my homework though. She would remind me to eat and drink for sure. She would mix Bournvita, a malted drink mix and sugar in boiled fresh milk in a stainless steel glass and put the glass in cold water to cool it down to just the right temperature for me to drink. It wasn’t because I wouldn’t do this myself, but if I were to be running late, she was afraid I would go to school without drinking my daily morning dose of milk. The same routine continued in the afternoon after I came back from school. She would heat the milk from our green meat safe and then cool it down after mixing in just the right amount of Bournvita and sugar. Hot liquids are served in rimmed stainless steel glasses in India. The rim is cooler for a good hold without burning hands while enjoying delicious Indian filter coffee or chai. It would have been easier for అమ్మ (Amma to make extra coffee and chai for me when she was making them herself and నాన్న (Nanna). But, she would say coffee and chai weren’t healthy for growing children and milk was the best. I didn’t have coffee or chai until I was in college. I have fond memories of drinking chai with friends at my hostel in Visakhapatnam. We hung out on our hostel grounds drinking chai in the evening.

అమ్మ (Amma) didn’t pack lunch for me to take to school. I came home to eat lunch everyday. It would have been easy to make extra upma, dosa, or puri and have me pack leftover breakfast to take to school. But she didn’t like the idea of eating breakfast which she didn't think was a complete meal at lunch time. Hence, I would come home for lunch every afternoon and go back to school for the afternoon session. By the time I came back for lunch, అమ్మ (Amma) and నాన్న (Nanna) would have had their lunch. She would be waiting for me while reading the newspaper or a book. She would sit with me while I had lunch making sure I ate a good meal.

She would comb and braid my long hair every single morning until I went to college. Rain or shine my two braids looked perfect and immaculate while I lived at home. The only thing I had to do was to keep my head straight while she applied oil to my hair and scalp, combed, and braided my hair. At the end, I had to hand her the straightened and rolled up hair ribbons back to her when she was ready for them. For a very long time, she braided my hair into two long braids folded in half so they didn’t dangle down to my knees. She washed my hair on Sundays with కుంకుడుకాయ (kunkudu kayaa is India soapberry in Telugu) juice and dried it with సాంబ్రాణి పొగ (sambrani poga is sambrani smoke or dhoop in Telugu)). We bought కుంకుడుకాయ (kunkudu kayaa) in large quantities and crush the before soaking them to extract the soap.

కుంకుడుకాయ (kunkudu kayaa) has antioxidants, amino acids, antifungal, and antibacterial properties. It removes bacteria and dandruff, promoting strong and silky hair. It prevents hair loss. There is no free lunch and కుంకుడుకాయ (kunkudu kayaa) isn’t friendly to the eyes as eyes become red and watery, if juice gets in the eyes while washing hair. Sambrani is balsamic resin from trees which is a commonly used ingredient in అగరబత్తి (agarabatti is incense stick in Telugu) and haircare. It was nice and relaxing to get my hair dried as I laid down on a cot half asleep with my hair dangling down while the సాంబ్రాణి పొగ (sambrani poga) rose up from a small clay plate in which it was being burned. My hair was thick and long so the ritual took up a good part of my Sunday morning or the afternoon. She would apply coconut oil infused with గోరింటాకు (gorintaku is henna in Telugu) powder to my hair.

అమ్మ (Amma) was proud of my long black hair and took great care of it. She very much enjoyed the praise and adoration from people who would say how beautiful and long my hair was. However, the praise came with a price. She thought all of this attention and దృష్టి (drishti) was bad. దృష్టి (drishti) means sight in Telugu, however it also means, “evil drishti or bad drishti”. Almost all Indian languages have a name for the concept of దృష్టి (drishti). In Hindi it is बुरी नजर (buri nazar), bad sight. When people admired my hair, clothing, or how I looked, అమ్మ (Amma) would politely thank them. As soon as we got home, she would be ready for her దృష్టి తీయడం (drishti teeyadam) ritual which means removing the ill effects of the దృష్టి (drishti) or bad drishti. She was armed with two types of దృష్టి తీయడం (drishti teeyadam) rituals, one for minor దృష్టి (drishti) incidents at a lower Richter scale and a second elaborate one for major ones.

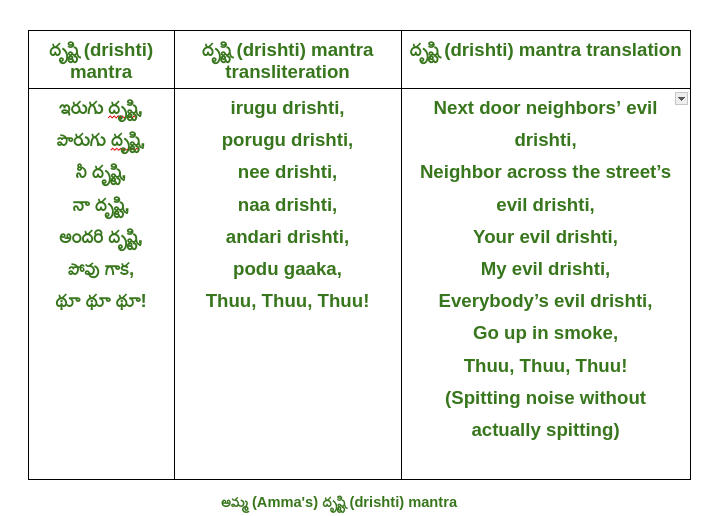

The minor ritual involved taking a fist full of sea salt crystals and a couple of dried red cayenne peppers in her right hand and circling it around my head three times clockwise and three times anticlockwise while reciting the దృష్టి (drishti) mantra. She would then move her fist up and down in front of my face and body and immediately throw it away. I think this was a simplified ritual. Some people would throw the spent salt and peppers that absorbed the evilness in hot coals or a pan to have them go up in smoke for the full effect. Everybody's eyes would be watering with the pungent pepper fumes. The potency of the fumes from the pepper demonstrates the bad potential of the దృష్టి (drishti) the ritual removed successfully.

A more elaborate ritual was reserved for serious దృష్టి (drishti) incidents. She would make a long wick out of an old piece of cloth, and soak it in cow ghee or oil used for lighting pooja diya. She would then hang the wick at the end of అట్లకాడ (atlakada is a flat spatula used for dosa making). She would hold the అట్లకాడ (atlakada) with her right hand with the wick facing me, circling it around my head, three times clockwise and three times anticlockwise while reciting the దృష్టి (drishti) mantra. She would then move the wick up and down in front of my face and body. She would then light the wick with a matchstick. How brightly it burned was an indication of how strong the దృష్టి (drishti) was. The burnt wick was thrown away after commenting on the potency of the దృష్టి (drishti).

Every birthday would end with either a minor or major దృష్టి (drishti) ritual after receiving praise for my beautiful new clothes she spent weeks stitching for my special day. The number three is very important in circling around the head and also ending the mantra saying, థూ (Thuu) three times. The number three is auspicious in the Hindu culture.

I am very lucky indeed to have a mother who was very protective of me, watched out for me, and saved me from దృష్టి (drishti) during my childhood. She continues to be protective and watches out for me even now. When she came to visit us, it was hard for her to watch people admire and praise her grandsons without taking measures to remove the ill effects of their దృష్టి (drishti). I would ask her to perform her దృష్టి (drishti) rituals for my kids to put her out of her misery.

The only real chore I took on was keeping an eye on clothes as they were drying in the sun, in case it rained, folding and putting them away once they were dry. I enjoy folding clothes even to this day. The act of turning a pile of clothes into neatly folded stacks is very satisfying. I would run and bring clothes if it started raining and hang them back on the clothesline once it stopped raining. I would help అమ్మ (Amma) with any chores and నాన్న (Nanna) if I was asked. నాన్న (Nanna) needed help when he was installing ceiling fans, tubelights, fixing and maintaining his scooter, or keeping track of how the village cows were doing after they were artificially inseminated with the prized Ongole bull semen. For the most part, they let me enjoy childhood with minimal chores. They used to say, “this is the time for you to get an education and have fun. You have to do all these chores all your adult life anyway and that can wait”. I later found out from a book I read that my parents both had this philosophy of childhood was for fun in common with the Innuit culture on the other side of the globe.

Back to my absentminded teenage life, a house we lived in during my 9th and 10th grades had a detached kitchen. We kept the kitchen closed when not in use and locked at night or when we were away. We used padlocks on all of our exterior doors and an interior door if we had valuables stored in that room. All the doors had a sliding latch and even if the door wasn't padlocked, the door would be latched. One morning, అమ్మ (Amma) asked me to close the kitchen door so crows wouldn’t get in. I closed the door and went back to whatever I was doing. After a while she found the kitchen door padlocked. She was carrying something to the kitchen and she was rather annoyed that the door was locked. She called me and asked me why the door was padlocked. I said, “to keep the crows away”. She could not continue to be angry at that point and burst out laughing and said “చదివిస్తే ఉన్న మతి పోయినట్లు (chadiviste unna mati poyinatlu)”. I was teased to no end for several years after that and the teasing continues even now when a right opportunity presents itself.

The phrase, “చదివిస్తే ఉన్న మతి పోయినట్లు (chadiviste unna mati poyinatlu)” is used to describe absent minded people. It was used very aptly when I had padlocked the door to keep crows from getting into the kitchen. In my defense, crows are very intelligent and I think I was very wise to padlock the door. What if they figured out how to unlatch it with their beaks?

Another time, she shouted at me to stop, to save me from chopping my finger off as I was just about to cut a mango with the sharp edge of the knife facing up. She then snatched the knife away from me and proceeded to cut the mango. This incident was scary and made me start paying attention and not be distracted with my head in the clouds all the time.

I still have my absent minded moments every now and then. One such incident happened on a trip to visit a friend with my younger one. He was about eleven years old. On the way in, I dropped my driver's license when we were going through security. Thankfully, an agent noticed it and handed it to me. On our way back, I left boarding passes on a counter when we went to get coffee and croissants. A fellow customer saved the day by bringing it to my attention. We made it to the gate with our boarding passes and I set them down on a chair next to me. We then moved to the boarding line waiting for boarding to start as we sat on our wheeled suitcases trying to balance ourselves. The boarding passes were still on the chair. A fellow passenger came to our rescue letting me know that I left my boarding passes on the chair. At that point my son turned around, snatched the boarding passes from me with a smile and took charge of keeping them safe, after giving me a look of surprise and exasperation. Our fellow passenger who saved the day, couldn’t help but smile as he watched this interaction. We all had a great laugh. My son won't let me forget this incident. When the right opportunity presents itself, he says with a smile, “Mom! Remember the driver’s license and boarding passes incident!”. He wouldn’t believe me when I say this never happened before and I am a careful person.

I still daydream and lose myself reading a book. As I write this story, these memories are coming back to me like gentle cascades washing over smooth rocks. When I hear the “చదివిస్తే ఉన్న మతి పోయినట్లు (chadiviste unna mati poyinatlu)” sameta, I remember my absent minded incidents and remind myself to be careful and pay attention to be safe.