Veranda Tales-Point of no return

Storytelling has been an integral part of my life since childhood. I grew up listening to stories during the hot summer evenings and nights with my cousins. Mothers and grandmothers would gather all of us children for story time. It was usually pitch dark except for a very faint light coming from the flickering candle. Power cuts were as frequent as the hot and humid summer days. We all spread out on a cool concrete floor or bamboo mats on the veranda intently listening to fascinating stories about kings, queens, princes, princesses, and peasants alike. Stories about love, life, families, and people entertained and taught us life skills. These stories transported us to distant worlds, strange yet familiar. Often the same story told by two people sounded different as storytellers added new twists and turns adding their personal style and flair to the stories.

Storytelling wasn’t limited to summer evenings and bedtime. I was surrounded by adults who didn’t pass up an opportunity to share their wisdom using the art of storytelling. These rich vibrant oral traditions include songs, poems, stories, and సామెతలు (Sametalu are proverbs in Telugu). Men and women sing songs as they work in the fields, grinding grains and spices and doing other daily chores at their homes. Stories are often used to teach important life lessons, interpersonal skills, and survival skills. These stories and the time spent listening to them made our lives richer leaving an impression on me. This series is all about reliving those memories as I share these stories.

తాంబూలాలిచ్చేశాను, తన్నుకు చావండి

Arranged marriages were the norm for the longest time in history in cultures across the globe and continue to be practiced today in some cultures such as India. Majority of the marriages in India are arranged by parents of the bride and groom irrespective of which religion they practice. They follow the ancient concept of marriage according to ancient Indians in which the bride is given away as a gift. The term కన్యాదానం (kanyadanam) means, “donating a maiden”. The concept of giving the bride away is not unique to Indian culture. Brides are given away by their fathers in western marriages as well. It is very important for a bride in America to have her father walk her down the aisle to the altar where the groom is waiting.

The ancient Hindu text, Atharvaveda, is believed to have been compiled around 1200 BCE – 1000 BCE along with Samaveda and Yajurveda. Atharvaveda is a compilation of atharvāṇas (rules) for everyday life spanning various aspects of daily life. Atharvaveda identifies eight forms of marriage - Brahma, Daiva, Arsha, Prajapatya, Gandharva, Asura, Rakshasa, and Paishacha. The first four are considered ధార్మిక్ (dharmic) or righteous. The other four are accepted and the last three are considered అధార్మిక్ (adharmic). Brahma, Daiva, Arsha, Asura, and Prajapatya type marriages are arranged by parents with slight variations on who initiates the proposal.

Gandharva marriage allows a couple to choose to marry without consent from their families. It is similar to the weddings in Gretna Green, Scotland to work around the Clandestine Marriages Act 1753 preventing couples under the age of 21 marrying in England or Wales without their parents' consent. As it was still legal in Scotland to marry without such consent, Gretna Green became a marriage haven for couples to elope to marry. References to couples eloping to get married in Gretna Green can be found in Jane Austen’s books. Gandharva marriage is as simple as exchanging garlands and pronouncing commitment to each other. There are several accounts of Gandharva marriages in Mahabharata, an Indian epic. This is a modern day equivalent of common law marriage in the USA.

కన్యాశుల్కం (kanyaasulkam roughly means, bride price in Telugu) is the common element in Asura and Arsha types of marriages. కన్యాశుల్కం (kanyaasulkam) is the money or goods paid to the bride’s family in exchange for the bride. The big difference between Arsha and Asura is in the amount of money exchanged for the bride. In Arsha marriages the కన్యాశుల్కం was nominal and affordable, whereas in the Asura type marriage, bridegroom paid everything he owned in exchange for the bride.

కన్యాశుల్కం (kanyaasulkam) has been replaced by వరకట్నం (varakatnam is dowry in Telugu) tradition, where money, property or jewelry paid to the bridegroom's parents. The dowry tradition is relatively new which came into practice in the 1950s. It continues to be practiced in India, even though the Dowry Prohibition Act enacted on July 1, 1961, prohibits exchanging property or valuables at the time of marriage.

Majority of marriages in India are arranged by parents and even when a couple picks each other, they work with their parents to arrange marriage for them. The difference is in how they find each other. This has been practiced from eons where parents have been finding a suitable partner for their sons and daughters. Parents come to visit prospective brides and their families with their son. The visit is to assess if there is a good match between the families and the prospective couple is called పెళ్లి చూపులు (pelli chuupulu) which translates to “marriage looks''.

Even before this formal visit, families find out about each other to see if the visit is worth their while. Prospective bride and groom would have seen photographs of each other. Before the advent of photography, this would have happened informally by stealing a glance. In majority of the cases, they first saw each other at the altar. My maternal grandparents lived in the same neighborhood and attended the same school. My maternal grandfather was given a choice of two prospective brides and he chose my grandmother. She took care of him as he was bedridden for a good part of their married life. My paternal grandparents didn’t know each other before their marriage. My parents met for the first time at the altar to get married having only seen black and white photographs of each other. My husband’s father managed to sneak a peek at his prospective bride, while she was visiting a mutual relative. He managed to get up on the terrace where he had the line of sight to where she was sitting with women in the family. Even after 50+ years of marriage the mention of his having gotten a glimpse of her before they got married makes my mother-in-law blush.

పెళ్లి చూపులు (pelli chuupulu) is an occasion for the two families to meet and have the prospective bride and groom meet in the presence of their families. Some families allow them to talk in private and some don’t. Once the families determine they have an alignment, they move forward to exchanging తాంబూలాలు (taambuulalau) to formalize and make a commitment to the upcoming nuptials. తాంబూలం (taambuulam) is a Sanskrit word. It is an arrangement of వక్కపొడి (vakkapodi) and coconut decorated with పసుపు (pasupu is turmeric Telugu) and/or కుంకుమ (kumkuma) placed in a bed of తమలపాకు (thamalapaaku). వక్కపొడి (vakkapodi is betel or areca nuts) and తమలపాకు (thamalapaaku) is Betel or Piper betle leaf in Telugu). This is a significant and final step which will lead to a marriage between the prospective bride and the groom in Hindu tradition. Mangni is an equivalent tradition among Indian muslims to mark the engagement by exchanging jewelry. There is no turning back after the final step and it is considered very bad to do so.

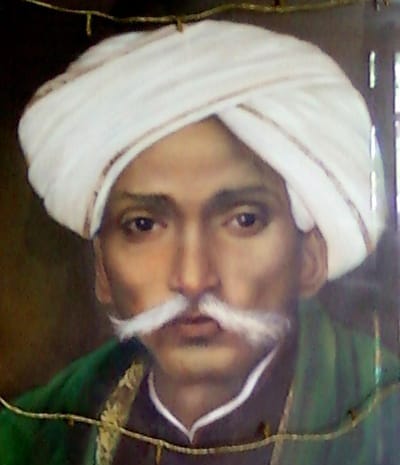

Before కన్యాశుల్కం (kanyaasulkam) went out the door, it took an ugly turn where parents were getting their young daughters married off before they reached puberty to very old men in exchange for money. These old men died soon after the marriage leaving young widows to live the rest of their lives dependent on their parents and brothers. There were several reformist writers who helped fight this societal evil and managed to put an end to this practice. One such writer who was instrumental in the quest to eliminate the practice of కన్యాశుల్కం (kanyaasulkam) was Gurajada Apparao. He spread his reformist and feminist message through his plays and songs.

In his play aptly named, కన్యాశుల్కం (kanyaasulkam), he tells the story of a young 10 year old girl who was being forced into marriage to a very old man by her father who did the same to her older sister. His wife and his now widowed daughter tried to talk him out of repeating the mistake. His wife tried to get help from her brother to talk sense into her husband and reconsider the decision to marry her daughter off to an old man who was ready to die any minute. In this play, the father says, “తాంబూలాలిచ్చేశాను, తన్నుకు చావండి (thaambulalu ichesanu, thannuku chavandi”), when he was asked by his wife and brother-in-law to reconsider the decision. He was saying, “we exchanged తాంబూలాలు (thaambulalu) and this decision can no longer be changed. The play ends in the girl being rescued by a clever plot by mother, and other family members by switching the bride with a young boy, thereby saving the girl. The old man ends up marrying a young boy only to be made fun of later in a fitting end to the old man’s and the father’s greed.

Gurajada Apparao ups the ante in his song, పుత్తడి బొమ్మ పూర్ణమ్మ (Puttadi Bomma Purnamma). In this compassionate and playful song, he narrates the story of Purnamma as a representative of young girls subjected to the evil practice of child marriage. పుత్తడి బొమ్మ పూర్ణమ్మ (Puttadi Bomma Purnamma) translates to “Purnamma, a gold doll”. He makes a compelling argument of evil in the society of sacrificing precious little girls in greed disguised as tradition. This phrase from this play has been absorbed into the Telugu language to be used to indicate finality of decisions and situations that can no longer be changed. It continues to serve as a reminder of the evil practices of the past that have been eliminated. It reminds us of the work of many like our Gurajada Apparao who questioned these evil practices in effective and peaceful ways leaving their mark on the history and the society for generations to come.