Veranda Tales-Nothing to see folks

Storytelling has been an integral part of my life since childhood. I grew up listening to stories during the hot summer evenings and nights with my cousins. Mothers and grandmothers would gather all of us children for story time. It was usually pitch dark except for a very faint light coming from the flickering candle. Power cuts were as frequent as the hot and humid summer days. We all spread out on a cool concrete floor or on bamboo mats on the veranda intently listening to fascinating stories about kings, queens, princes, princesses, and peasants alike. Stories about love, life, families, and people entertained and taught us life skills. These stories transported us to distant worlds which were strange yet familiar. Often the same story told by two people sounded different as storytellers added new twists and turns adding their personal style and flair to the stories.

Storytelling wasn’t limited to summer evenings and bedtime. I was surrounded by adults that didn’t pass up an opportunity to share their wisdom using the art of storytelling. The rich and vibrant oral traditions include songs, poems, stories, and సామెతలు (Sametalu are proverbs in Telugu). Men and women sing songs as they work in the fields, grind grains and spices and other daily chores at their homes. Stories are often used to teach important life lessons, interpersonal skills, and survival skills. These stories and the time spent listening to them made our lives richer leaving an impression on me. This series is all about reliving those memories as I share these stories.

సింగినాదం జీలకర్ర (singinadam jeelakarra)

నాన్న (Nanna is father in Telugu) would say “అదంతా సింగినాదమే (adanta singinadame) when he was talking about an event or incident that he thought was made a big deal out of for no good reason and didn’t deserve that much attention. సింగినాదం (singinadam) phrase means “It was all just a hype and not earth shattering”. I never really understood what it truly means. This phrase gets used by people in my family on occasion to convey that something isn’t as big of a deal as it was made out to be. It was used when a severe cyclone warning turned out to be a rainstorm that passed through with very little impact to people. When a movie that was released with a lot of fanfare turned out to be a waste of time to watch. When someone sang praises of a newly built movie theater or a restaurant, నాన్న (Nanna) would say “ఈయన సింగినాదాల రామాన్నే (eeyana singinadala ramanne)” which means, “He is exaggerating, it is a run of the mill movie theater or food at that restaurant isn’t that good”.

People in my family just say సింగినాదం (singinadam) and not the full form of the expression “సింగినాదం జీలకర్ర (singinadam jeelakarra). జీలకర్ర is cumin seeds in Telugu. సింగినాదం (singinadam) is a combination of శృంగం (srungam) and నాదం (nadam) which means sound of a horn. శృంగం (Sringam) is a Sanskrit word for horn. నాదం (nadam) is a Sanskrit word for sound or music. Both of these words are part of Telugu language which mean the same as they do in Sanskrit. It was originally శృంగనాదం (srunganadam) which evolved or devolved into a simpler sounding సింగినాదం (singinadam).

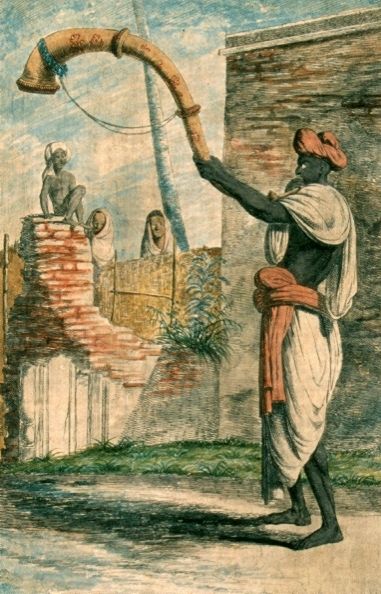

శృంగం (Sringam) is an ancient Indian musical instrument. It is a type of horn - a wind instrument. They were originally made of animal horns as horns were readily available in villages. Kings would have them made out of copper and copper alloys with ornate decorations. It was played at royal ceremonies, rituals, festivals, weddings and other special occasions. It continues to be played at weddings, rituals, and military and other music performances. When I first heard the full form of this expression “సింగినాదం జీలకర్ర (singinadam jeelakarra), I didn’t connect it to శృంగం (Sringam) and its నాదం (music) when I was growing up. I became curious about the origins of it and researched to learn the fascinating history behind this expression that spans several centuries.

Once upon a time, villages were raided by bands of dacoits. It was a frequent occurrence in which dacoits stole money, rice, grains, and other valuables from villagers. Villagers were left without money and more importantly food they were storing to survive for the rest of the season which was an immediate emergency. In addition, they lost the grains they needed to plant their crops the next season. They lost livestock as the dacoits often took whatever they could take with them. After several years of suffering through these raids, villagers started to watch out for impending dacoit attacks. They also learned to be prepared by building hiding places for their families, food, and valuables. They learned to tune into the signs of impending raids.

Dacoits came riding through the villages blowing their శృంగాలు (srungalu - horns). When villagers heard the సింగినాదం (singinadam) coming from afar, they knew dacoits were approaching the village. They started to quickly go into their hiding places with food and valuables they could carry. Dacoits took whatever was left behind. This continued for years and then villagers got tired of watching all their hard work of growing crops being lost to the dacoits. They decided to fight back instead of hiding. They already had the necessary tools to defend themselves. The same tools they used to till the land and harvest the crops, could be used to defend themselves. They held training camps to be prepared and ready to fight back. When they heard సింగినాదం (singinadam), vulnerable elderly, women and children in the village went into hiding leaving their trained men and youth to fight the dacoits. The army of defenders ran in the direction of the సింగినాదం (singinadam) to meet the dacoits head on. They were successful in chasing the dacoits away.

Over a period of time, dacoits found it hard to loot and steal when they raided villages. The villagers were fighting back and it was becoming a losing proposition for the dacoits. They stopped raiding and moved onto greener pastures. We don’t know what these greener pastures were. Maybe they fell in love with village people and decided to settle down, giving up their life of dacoity. Maybe villagers managed to convince the dacoits that it would be better profession to be a defender of villages than looting them. For reasons unknown, villages became safe from dacoits after successfully defending themselves time and again. However, సింగినాదం (singinadam) was inextricably linked to the danger of dacoits in their collective minds. Whenever they heard సింగినాదం (singinadam), they continued to run in the direction of the sound to meet danger head on. As years went by, సింగినాదం (singinadam) and the dacoit raids became few and far in between and stopped for good.

After several tens of decades, one fine afternoon, villagers heard సింగినాదం (singinadam) coming from the direction of a nearby river. This was new to them. Dacoits usually rode from a nearby village in the opposite direction from the river. Dacoits didn’t float down the river as it would make them far more vulnerable since it was slow and villagers could simply sabotage their boats. Villagers looked at each other and wondered what this could mean. In their minds, సింగినాదం (singinadam) coming from the river was far more dangerous. Could this be an invading army? They decided to take whatever they could find to defend themselves and ran towards the river. They heard stories of their brave ancestors defending themselves and were ready to do the same. When they reached the river, they saw జీలకర్ర (jeelakarra) merchants setting up their tents on the river bank to sell జీలకర్ర (jeelakarra) and other things they brought with them. The merchants were alarmed to see the armed villagers running towards them. Villagers were pleasantly surprised and bought జీలకర్ర (jeelakarra) from the mechants. Villagers figured out quickly that there was no danger and it was just జీలకర్ర (jeelakarra) to buy.

During those days, జీలకర్ర (jeelakarra) didn’t come neatly packaged in plastic bags waiting to be picked up on the shelves of a store. It was transported on boats on rivers from village to village to be sold. When they reached a village, జీలకర్ర (jeelakarra) merchants blew their శృంగాలు (srungalu - horns) to let the villagers know it was time to buy జీలకర్ర (jeelakarra) to spice their meat, vegetables, and soups. I love జీలకర్ర (jeelakarra) and use it generously in many of my dishes. It was a happy ending as the merchants were able to sell whatever they brought and villagers were happy to buy things that floated down to their river bank.

Since then, సింగినాదం (singinadam) expression started its second life as సింగినాదం జీలకర్ర (singinadam jeelakarra) as it was associated with జీలకర్ర (jeelakarra) merchants since then. When villagers heard the సింగినాదం (singinadam), they started saying, “It is just సింగినాదం జీలకర్ర (singinadam jeelakarra), there is need to be concerned”. It is still used even today to describe an ordinary mundane incident or occurrence which is made to sound extraordinary.

One might ask how is the drive through Florida Keys, I would say సింగినాదం జీలకర్ర (singinadam jeelakarra) people, it isn’t worth all the hype and excitement. సింగినాదం జీలకర్ర (singinadam jeelakarra) reminds me of నాన్న (Nanna) and the expression on his face when he said it.